A River Runs Again

India’s natural world in crisis, from the barren cliffs of Rajasthan to the farmlands of Karnataka

(Author: Meera Subramanian)

Meera Subramanian’s book stitches together stories of activists and common folks who are working to address India’s environmental problems into a documentary-like narrative. She assays several different yet interconnected problems and gathers interviews, thoughts, ideas, and passions into seamless strings of essays. She has traveled widely in India for her work.

Open fire wood stoves and biomass burning are commonly used in India to cook meals and heat water for centuries, and still remains the most prevalent in rural areas. The smoke, especially of indoor wood stoves, can wreak havoc on the people living in the house, especially women and young children. She analyzes the international efforts to bring safe and less polluting cooking stoves to India and masses around the world. Many of these efforts have not come to fruition or reached scale because either the stoves don’t meet the demands of daily cooking, or simply women still prefer traditional methods of cooking on open fires to unreliable or short-lived cooking stoves.

The near-extinction of South Asian vultures is another ecological tragedy she writes extensively about. Subramanian has written widely on the subject in publications and compiles much of her research here into concise prose. The birds have filled a very important niche in the ecology of the country, keeping carcass dumps and carrion clean of streets and towns. Now with the commonly used anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac killing off most of the birds, she visits people trying to keep them from dying off. Farmers use the veterinary version of the drug, and when vultures eat the carcass of that animal, it proves fatal and they die shortly.

In the essays and reportage she details investigations into the decline of India’s vulture population, almost to the point of extinction, and how this will affect the biodiversity and natural order of things in the country. Vultures are the street cleaners of carrion and carcass dumps. Who will do this natural job if they are all gone? Their extinction would create a vacuum in the natural order of things that would be irreplaceable.

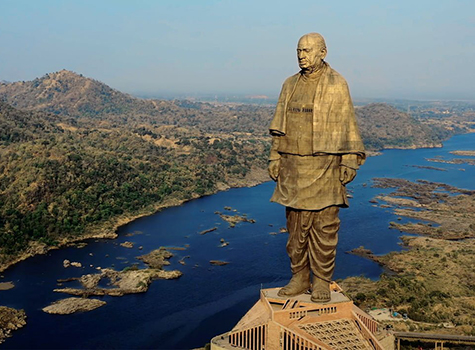

In another of India’s dilemmas, she also writes about the “Rainman of Rajasthan” who is helping build dams to collect rainwater into pools that supply water for farmers and replenish wells that are tapped during the dry seasons. She writes that India’s problems can be solved via localized micro projects like those small dams, rather than massive macro projects. Sustainability efforts on the micro levels, customized to local areas and environments, are the solution to India’s long-term environmental and water and land protection efforts.

Her reportage is not dry, but filled with stories of micro-level works of several people she profiles. They are all unique characters telling the greater story of India. From farmers returning to organic farming, to activists trying to bring back vultures, rural dweller building small dams to harvest rainwater and replenish wells, all people profiled in the book present a promise of positive possibilities and solutions. They are among the activists and farmers, along with government workers, trying to keep India from falling into an irreversible environmental disaster. It could be depressing to read about seemingly intractable problems, but Subramanian showcases positive efforts at mitigating these problems and passions of people seeking to make India into a better place for all.

The last chapter of “A River Runs Again” seems out of place with the rest of the narrative. The book covers environmental dilemmas throughout, but in the last chapter Subramanian talks about women’s sexual health and reproduction activists. It is a fine and necessary discussion, but doesn’t quite fit with the rest of the book and feels like an afterthought. It is very informative, but it could be a part of another book dedicated to such efforts and reportage.